‘+’ or ‘-’ and sometimes ‘+/-’

Only twelve humans have ever touched the surface of another galactic sphere. One of them, Astronaut Charlie Duke, once gave a homily to my high school chapel. While one might have expected Duke to deliver a cliché “you can reach for the skies” exhortation to my pimple-faced coevals, he instead shared a fascinating disquisition on experience.

It was really neat. (This cheap modifier will make sense later.)

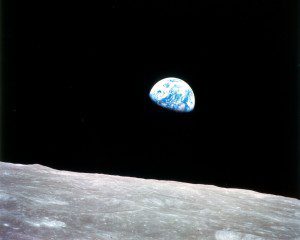

Mr. Duke surely did not intend to deliver an existentialism lecture that would straighten Jean-Paul Sartre’s eyeballs, but that’s about what happened. Duke attempted to convey the breathtaking phenomenon of standing on the lunar landscape and beholding our own Little Blue Planet floating in the celestial foreground.

He explained that after he set the record for a lunar surface stay—more than 70 hours—he returned to Earth. And found himself really bored.

Duke was mired in a thick, intergalactic-postpartum funk. After all, once one has driven a dune buggy on the moon’s rough Cayley Plains, what else is there to do? (Other than bed Eva Longoria.)

There was actually a positive end to Mr. Duke’s message. He turned his soul over to God. And who can blame Duke for climbing a metaphysical stepladder at that point in his life? At least it’s more affirmative than the end George Eastman chose for himself.

George Eastman was the 19th-century American entrepreneur who founded Eastman Kodak. He invented the first practical portable camera, which earned him hundreds of millions of dollars at a time when such wealth was simply unfathomable. Eastman’s invention ushered the world into the Iconic Era. Not bad for a high school dropout.

But facing a Charlie Duke-like existential crisis in his latter years—probably brought on by the realization that he was too old to try out for his beloved New York Yankees—Eastman shot himself in the heart, leaving behind undoubtedly the most succinct suicide note in human history:

“My work is done. Why wait?”

Nice.

Next let us consider the life of Nobel Prize-winning scientist Kary Mullis, who attended Columbia’s own Hand Middle School and Dreher High School. Mullis was awarded the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his invention of Polymerase Chain Reaction, a biochemical technique that replicates DNA without the use of a living organism.

Mullis’ was one of the more controversial Nobel Prizes ever awarded, and a rumor still abounds that Mullis showed up with a gun and forced the company he worked for, Cetus, to give him full credit for his invention.

Faced with the apex of scientific discovery and accomplishment, Mullis, unlike Duke or Eastman, chose neither God nor Death. He instead volunteered to be a forensic witness at the O.J. Simpson trial, then quit his job and became a full-time California surfer dude.

Nifty.

We are taught in grammar school that every essay needs a narrowed point. So I suppose I had better grind one out with my remaining 300 words.

Originally I desired to write about language’s general inability to match superlative experience. That is, when one remarks about something overwhelmingly positive, one typically says, “Neat” or “Nice.” One may even venture into the territory of “Amazing!” or “Cool!” Shakespeare might have exclaimed, “Mine spirit is convivially enraptured.”

For a negative experience, one utters, “How awful!” or even “O, the humanity!” Shakespeare again: “Life is a fen-suck’d fog!”

Be it grandiloquent or banal, what one utters at such a moment is simply a binary “+” (positive) or “-” (negative).

Rarely, one encounters something of the “+/-” experiential category.

For instance, during a blowjob from a hooker, a man might have a heart attack and die. The prostitute explains what happened to a paramedic, who declares, “Tragic, but what a way to go!”

That’s what I wanted to write about, but then I started thinking about the rare person who leads an entire life of superlative experience. What happens when such a person reaches the pinnacle of what life can possibly offer? Charlie Duke, George Eastman and Kary Mullis all came to mind.

I suppose you’re still looking for the point of this essay.

When Charlie Duke finished speaking to my high school chapel, I approached him and asked him to sign my Bible. Duke wrote a lengthy personalized inscription. But of all things, he forgot to sign his name. Thought I’d just leave you with a sort of “~”.

My work is done.

[This piece was published in Columbia City Paper in January 2007. I like this one. Have a “+” day!]

- Posted by

Arik Bjorn

Arik Bjorn - Posted in Arik's Blog

Dec, 21, 2013

Dec, 21, 2013 No Comments.

No Comments.

I think Uber Nights is the perfect bathroom book. If there are any public libraries out there listening, I think they should put a copy in every stall.

-Read more about Uber Nights